- HOME

- HISTORY

- PEOPLE

- LAND

- BUILDINGS

- CONTACT

STOULTON THROUGH TIME

ANGLO-SAXON STOULTON

IN THE EARLIEST OF TIMES - STOULTON PEOPLE LOOKED WESTWARDS TO KEMPSEY!

This story starts with the creation of the Diocese of Worcester in 681.

Worcester was the centre of a great Christian Diocese - it covered the tribal lands of the Hwicce people and included all of Gloucestershire east of the River Severn; south Warwickshire and all of Worcestershire except the very far west. In those early days Kings and the wealthy gave land to the Church and Christian monastic estates developed. One such monastery was in Kempsey, a place strategically positioned by the River Severn.

There was an early Christian monastery in Kempsey. In 799 Coenwulf, King of Mercia, gave land to the monastery at Kempsey. The monastery was made free from all secular services, except military service and the building and repairing of bridges and strongholds. In 818 the bishop decreed that all the Worcester monasteries belonged to the monks of Worcester. In those days the bishops were also monks.

Exactly when the distant and distinct farming settlements of Stoulton, Mucknell and Wolverton were included in the monastic estate, organised from Kempsey, is unknown but it is known that in 840 Bertwulf, then King of the Mercians, restored Stoulton to the Bishop of Worcester - who had been unjustly deprived of it.

WHY WAS STOULTON WAS SO SIGNIFICANT?

Perhaps the answer lies in its unique place-name. Translated from Old English, “Stoulton” means ‘the place of the stool or seat’ but the seat of what? Could Stoulton have been an ancient seat of authority and administration? Today travellers in their cars on the A44 rarely notice the slight rise and fall of the road as it travels over “Low Hill” but this is a special place!

Low Hill is considered to be an historic meeting and mustering place, first of Oslaf, a Bernician prince and later of the Bishop of Worcester’s triple "Hundred of Oswaldlow”. If there is truth in this, then the site has indeed been a place of some significance but there is little to show for it today. in Anglo-Saxon times the Hundreds were outdoor meeting places where freemen who met together every three or four weeks to organise and enforce law and order, muster troops and to collect taxes. This was the place of the Hundred Court and the gallows! Free men, accompanied by their retinues, would need food, shelter in inclement weather and, if they had to travel a distance, accommodation. Quiet now, this place would have been a hive of activity and gossip.

Perhaps this helps to explain why in 984, Bishop Oswald hived off land from the farming settlement of nearby Wolverton and settled his sister and her husband in Little Wolverton. Little Wolverton lies just off today’s A44, travelling east, just before it travels out of what was once the Bishop’s land. In those days this was a route that connected Worcester to the bishop’s Gloucestershire estates, and, it was a Salt Way. Packhorses carrying salt to the manors and markets on the way came back laden with wood, fuel for the salt pans in Droitwich. They must have needed protection from thieves and robbers.

With so many secular responsibilities, the Bishops of Worcester needed the help of secular supporters he could rely on. Little Wolverton continued to be used for supporters of successive Bishops right up to the Norman Conquest.

THEN THEY LOOK NORTHWARDS TO WORCESTER!- WHY THE CHANGE OF DIRECTION?

In the time of Edward the Confessor the Stoulton harvest, which had previously been taken to Kempsey, was assigned to the monks of Worcester. Before the Norman Conquest all the Bishops of Worcester were monks but, unlike their brothers in the great Monastery of St. Mary in Worcester, bishops lived a more peripatetic life travelling around their Diocese, living on their estates and eating the produce of their land. It made sense to divert the harvest from Stoulton, Mucknell and Over Wolverton to Worcester.

For centuries the road between Worcester and Stoulton stopped at a T junction with the Stoulton to Wadborough road. Stoulton, village and parish, had for hundreds of years looked westward to Kempsey, it still did for church purposes as the local Parish Church was in Kempsey. Now the traffic also went north to Worcester.

THE NORMAN CONQUEST

CONQUEST BY THE NORMANS!

In 1066 things changed yet again. The new sheriff of Worcester, Urse d’Abitot, seised the farming settlements of Stoulton from the Bishop and used them for his own benefit. If the Hundred Court really was in Stoulton this would not be so surprising. As Sheriff Urse was the link between the county of Worcestershire and King William, he had legal, financial and military responsibilities. However in Worcestershire, where so much of the county was under the overlordship of the Church, carrying out these duties was difficult and costly. Holding Stoulton, even with the bishop as overlord, gave access to the activities of the bishop’s triple Hundred of Oswaldlow.

STOULTON NOW LOOKS TO THE SOUTH.

Post conquest life for the food growers of Stoulton probably carried on much the same as before the conquest except they were no longer working directly for the bishop or the monks of Worcester. Their rents and harvests went to Urse d’Abitot, the Norman Sheriff of Worcester and his descendants the Beauchamps.

The Beauchamps were great Worcestershire landowners, they held some of their manors as tenants in chief but others, including Stoulton, as ‘under tenants’ of the Bishops of Worcester. The bishops owed Knights Service to the king and transferred this responsibility to the Beauchamps. In the early days of their ownership, the manor of Stoulton was a demesne manor. The harvests went south to the castle at Elmley on Bredon Hill, the home of Beauchamps. They were an upwardly mobile family, by the early 14th century they were the Earls of Warwick living in Warwick Castle. These were turbulent times in national politics, costs were high and the old order was changing. The value of Stoulton manor was now seen in a new economic light.

Knights and valued retainers needed to be rewarded, pieces of land went out on lease. Finally in 1389 the whole estate, coupled with the Wadborough Park estate was leased to the Duke of Kent. At some stage the management of Stoulton had been coupled with the management of Wadborough Park. The combined estate, known first as Wadborough with Stoulton and later as Stoulton with Wadborough was, from now, to follow the same path. The Wadborough Park, which included the deer park, was not the part of Wadborough included in the lands of Pershore Abbey.

A TIME OF GREAT, BUT DISTANT, LANDLORDS

The influence of the Beauchamps, as the Earls of Warwick, came to an end with the Wars of the Roses. The new Earls of Warwick and landlords of Stoulton came from the Latimer family They moved in high circles, they did not reside in Stoulton or Wadborough. However they sent their stewards to collect the rents. The 3rd Lord Latimer did leave local property to his friends and servants John and Robert Leighton. When Lord Latimer died his wife, Catherine Parr married Henry VIII and became Queen of England!

The food producers of Stoulton continued to till the land to the rhythm of the seasons: over in Little Wolverton life was pretty much the same. After the Black Death there were more wage-earners and the enclosure of some of the medieval strips had begun.

Everyone was legally required to attend church on Sundays. From the early 12th century this meant Mass in the new Chapel of Ease in Stoulton village but, it was still necessary to make the five mile journey to the Mother Church in Kempsey for the major festivals and for funerals. St. Edmund’s must have been a popular place where Stoulton people were happy to spend their money buying candles and church vestments. In the early 14th century they even replaced two of the old round headed Norman windows with larger windows with pointed arches and beautiful tracery, they let in more light.

TUDOR STOULTON

TITHES AND THE PARISH VESTRY

Everyone paid rent, taxes and tithes. The tithes was a tax that went to the church. In Stoulton, from time immemorial, the tithes had gone to the monks of Worcester where they were used to help care for the sick and destitute. But in 1473 Bishop Carpenter had other ideas, Stoulton tithes would go far away, to support the Bishop's newly refurbished College of Secular Canons in Westbury-on-Trym (now in Bristol) and so it remained until the Reformation.

The Reformation affected the small parish of Stoulton just like it did other communities up and down the land. The monasteries had gone, there were new regulations engaging local people in the care of the sick and the relief of the poor. The role of the Church Wardens grew ever more onerous. The annual Parish vestry meeting elected the parish officers who would be responsible for the church, take care of the sick and destitute, the roads and law and order. The Stoulton records record the names of the families, yeoman farmers, who voluntarily undertook these responsibilities year after year.

17TH CENTURY TURMOIL

Certain characters step out from history, the Reverend George Allen is one of them. Born c 1580 he began his ministry in Stoulton in 1608 and died in office in 1657. He lived through turbulent times of great change in Stoulton. He steered his flock through the sale of the Stoulton Estate, the establishment of a new lord of the manor Sir Samuel Sandys of Ombersley, the destruction caused by the civil wars and early years of the Commonwealth. During all that time he kept the community together and still at the age of 80 he was collecting local rents. Why? The full story behind this has yet to be uncovered but in the church records both the church and the parsonage house are described as being in a very bad shape and in need of considerable attention - the church tower burnt down and cows were living in the parsonage kitchen.

There is much to explore in the archives of this period. A 17th century plan of the Stoulton Estate created for the sale of the estate in 1636 confirms the belief that there was property on the same sites as in seen in Stoulton village today; the big difference being that there is still no road going south, down from Stoulton village to Hawbridge.

A LOCAL LORD OF THE MANOR

Sir Samuel Sandys, who purchased the Stoulton Estate in 1636, had to mortgage it as a consequence of his position as a prominent Royalist in the Civil Wars. The full details of this mortgage are still unclear but the papers are in the archives of Eastnor Castle in the care of the family that finally inherited the estate. In essence most but not all of the estate was purchased from Sir Samuel Sandys by John Somers of Claines. This prominent constitutional lawyer and politician became Lord Chancellor under James II and Lord Keeper under William III. He is particularly remembered for his role in the writing of the Bill of Rights, a sort of new Magna Carta. He amassed great wealth and the title of Lord Somers of Evesham but he died in 1716 without issue. His estate was divided between his two sisters but eventually it all went to Mary who had married into the Cocks family. Mary’s grandson married Margaret Nash, the only daughter of the wealthy Reverend Dr. Treadway Nash. Her marriage settlement included Wolverton and Windmill Hill farms bringing them back into an estate now called The Stoulton Estate.

200 YEARS OF STABILITY AND GROWTH

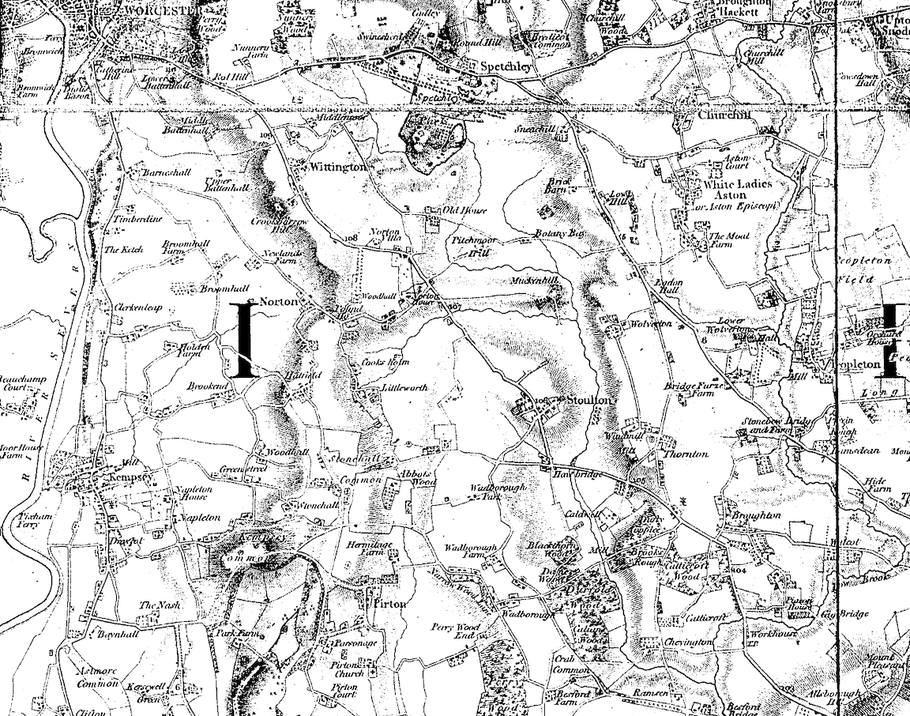

The Somers Cocks family of Eastnor Castle in Herefordshire were now lords of the manor of Stoulton. The second Baron Somers did much to reorganise the fields and farms of the Stoulton estate. He was assisted by a much respected and nationally recognised firm of Land Agents under the leadership of Nathaniel Kent. In 1774 Kent undertook a descriptive survey of the estate drawing a coloured plan of each farm, numbering the fields and commenting on the tillage and management of each. Kent believed that to maximise the yield from an estate it was prudent to have a specific ratio in the size of the agricultural units. Kent was employed by the estate for a number of years. It would seem that the enclosure of much of the old open fields system was undertaken without the need for Parliamentary involvement but that does not mean that there were no problems.

VICTORIAN STOULTON

When Lord Somers became Earl Somers and Eastnor Castle was built in the 19th century, the Stoulton Estate and particularly Stoulton Village flourished. Crucial to this development was the extension of the High Road down the road to Hawbridge. Stage coaches had been using the Old London road that crossed the bridge at Hawbridge, skirted round the steep slope of Stoulton bank, and ran along the boundary road between Stoulton and Wadborough towards Littleworth. This new road came straight out from Worcester, ran straight through the centre of the village and down the smoothed out slope of the bank, it was a fast route for stage coaches, and later for the cars that stopped for petrol at the new purpose built Motor House.. With an eye to the local economy the estate built a Coaching Inn with stables on the corners of Church Lane. The house now called ‘Mount Pleasant’ had its own brew house. Just down Church Lane the owners of a farm house with a malt house attached, now know as The Maltings, diversified. It was opened as a bakery and one of the first sub Post Offices in Worcestershire. Over the road was Stoulton Court Farm, a busy farm with many barns, stables and farm buildings. Over the High Road was Boxbush Farm and further down Froggery Lane was the Smithy. The semi detached agricultural workers cottages built at the turn of the 20th century were tied cottages for agricultural workers. Eastnor Castle employed and housed an estate carpenter in Stoulton, his correspondence with the agent at Eastnor adds local colour to the story.

Services in St Edmund’s, the Chapel of Ease built in stone in the early 12th century, had been bringing the farming community together for hundreds of years. It received permission to have its own small burial ground and employ a curate in 1529 but technically, in 1800, Stoulton was still an administrative district of Kempsey Parish. For centuries the Stoulton community had been functioning independently electing. It appointed its own Church Wardens, Offices of the Poor, Constables and Road Surveyors, all were volunteers elected at the annual parish vestry meeting held in the Church. Finally, in 1814, an Act of Parliament brought in by Lord Somers of Eastnor, made Stoulton an independent parish. Lord Somers was now Patron of St Edmund’s Church, he had the right to present clergy for bishop’s approval. Attendance at Church was high, the congregation came from all around the parish to the community’s only pace of worship. However, in the 1852 Census of Religious Worship, the curate reported that attendance from the more remote parts of the parish often depended upon the weather!

The humble parsonage house, which might have been the three bay house made ready for the curate in the mid 16th century, but was certainly the one with the cows inhabiting the kitchen after the civil war, had already been restored and upgraded in brick in the late 18th century. It was a popular clergy residence which was now to be extended further with the help of a grant from Queen Annes Benefit, and gentrified. To do this necessitated the dismantling of the Tithe Barn. Since the restoration of the monarchy, Stoulton tithes had gone to its patrons, the Dean and Chapter of Worcester Cathedral. Storage barns, especially tithe barns, had been an important part of Stoulton’s history but when Lord Somers became a leasee of the tithes he did not see any further need for it; in many places tithes were being commuted for cash and that was to be the case in Stoulton. The size of the building was recorded and a promise made that it would be rebuilt if ever needed and so the work on the house began.

The Reverend and Honourable James Somers did not stay long in Stoulton but he set in motion traditions that were to continue to enhance village life and put Stoulton on the map. He became a prebend of Worcester Cathedral and was able to organise for choirs, lay clerks and choristers, to attend special services like the re-opening of the church after the 1848 restoration. On that occasion a procession, which included many visiting clergy, local school children and choristers from the cathedral, left the old schoolroom to walk to the newly reopened church.

In the 21st century clues to earlier incarnations of village properties can be found in the house names, roof lines and frontages that hide old timber framed buildings but, there are still some secrets. One such secret is the cottage beyond the Old Vicarage currently named “The Tynings”. Who would guess that this beautiful old cottage was once called “Vicarage Cottage” and was home to the Church Sexton. That’s not all, in the early 19th century the bay nearest the track to the fields was a high barn like construction that housed the village school! The current residents remember the lofty interior with wood panelled walls and a gallery, rather like a minstrels gallery. The school was popular and children from large agricultural families round about walked into and out of Stoulton village on their way to and from school and Sunday school, except at harvest time when everybody went out into the fields to help with the harvest.

The coming of the railway in the 1850s changed things in the parish yet again. The Agricultural Depression of the 1880s impacted on Stoulton’s farms. Many farm labourers recognised an opportunity to grow fruit and vegetables and the railway meant that fresh produce could be in the markets of the Black Country the next day. The train station was actually situated just over the parish border in Drakes Broughton but close to Windmill Hill Farm and the few cottages around it. This settlement was to grow in the 20th century and there were several market gardeners in the vicinity but by 1986 the station had closed.

THE LORD OF THE MANOR IS A LADY!

A new village school opened in the building that is now the Village Hall in 1877. Part funded by Earl Somers and built on his land at the end of Church Lane but with a considerable local financial contribution. It also had a gallery where the younger children were taught. By the turn of the 20th century the school was stretched to bursting and an extension was planned. The lord of the manor was now a lady of the manor. Earl Somers’ daughter Isabella was married to `Lord Henry Somerset’ and she was known a ‘Lady Henry’. Records show her as having a keen interest in the village but changes were afoot. Lady Henry was a well know philanthropist and prohibitionist. The Somers Arms, the coaching inn, almost at once became a school for young ladies! Under her watch the Village School was enlarged but in the 1930s its facilities did not meet the more exacting standards of the times and the school was closed.

20th CENTURY STOULTON

THE END OF AN ERA

The Stoulton Estate was sold in 1917. Once again a plan of the estate was produced, it looked remarkably similar to that created in 1634, the field patterns had changed, a few houses had been built, or disappeared but the estate would probably have been recognisable to the 17th century buyer. Every house was described in the accompanying document each had, or shared, a well of water but, as today in the older parts of the village, every householder would have to look after its own sewage. Many farmers bought their farms and a new landowner entered the stage. Mr Deakin, fruit farmer of Norton Hall purchased Boxbush Farm, Mucknell Farm and Brick Barns farm. The 1921 census records the many local people who worked for him. Fruit was grown for jam and for canning, especially important during the First World War, but in 1936 the operation closed to be replaced by Smedleys who used the canning factory to can peas.

In Stoulton Village Mr T. Bomford purchased Stoulton Farm and many other fields to create the biggest farm in the parish. He was also the landlord of the cottages on the Worcester Road built by the Eastnor estate as tied cottages for agricultural workers. The Bomfords continued to farm in Stoulton into the 21st century. Then the farm was sold. The fields are still worked, owned by we don’t know who, but managed locally with farm machinery visiting three or four times a year to plough and harrow, spray weed and harvest. The Manor farmhouse has become a private residence and the farm buildings made way in the 1980s for a small housing development. Boxbush farmhouse is now three cottages and the farm old buildings and barns, are now beautiful modern homes. The smithy, now The Old Smithy, is still in Froggery Lane.

21st CENTURY STOULTON

The old village farms worked into the 20th century but are no longer working farms.‘Boxbush farmhouse has been converted into three cottages and Stoulton Court Farmhouse is now known as Manor Farmhouse and a small housing development was built over the old farm buildings in the 1980s The Bomfords continued to farm in Stoulton into the 21st century. Then the farm was sold. The fields are still worked, owned by we don’t know who, but managed locally with farm machinery visiting three or four times a year to plough and harrow, spray weed and harvest. The Manor farmhouse has become a private residence and the farm buildings made way in the 1980s for a small housing development. Boxbush farmhouse is now three cottages and the farm old buildings and barns, are now beautiful modern homes. The smithy, now The Old Smithy, is still in Froggery Lane.

The High Road through the Village has been a mixed blessing. It cuts the village in half, just like the railway cut the parish in half and changed the way people were able to keep in touch with each other. In the 21st century the cars that pass through the village hardly notice the small settlement on the hill but the children and old people who have to cross the road to catch a bus or post a letter certainly do. The Motor House occupies a prime position in the centre of the village. At one time cars and their drivers stopped for petrol or for a bar of chocolate but those days have long gone. Today Stoulton village remains a good place to live, those who live in the village are no longer farmers but professional people who appreciate the good communications that exist to travel quickly all around the country. There has been some housing infill but not enough to mask over a thousand years of farming history

Manor Farmhouse became a private residence and a terrace of three brick houses was developed from nearby farm buildings. In Frogery Lane near the old Boxbush Farmhouse, the old farm buildings wrecked by fire in the later 20th century have now been converted into modern homes. In Church Lane new 20th century housing infill has blended into village scape. Still the road has no pavements or street lighting , and there is a dearth of car parking space for visitors. However the Village Hall, the churchyard and and the 900 year old Church of St. Edmund still welcome visitors.